Let me first apologise for the long digression that was Parts II and III. I had not intended that but it just sorted of blurted itself out and forced me to write it. I wouldn’t say it was entirely unrelated to DEXOS, though, on reflection. But now, we are going to definitely get to the initially intended Part II, which now becomes Parts IV and V. Confused? You soon will be.

So this is where I go all properly extraterrestrial on you. Since that was the primary purpose of DEXOS, after all.

Besides, as part of my justification (as if I should need one – given this is my Substack), next to all my lovely subscribers from my sports clubs, who have heard me rambling on about all this before, I appear to have picked up a whole load of sci-fi fans on my Substack. Writers and readers. Well, I am very happy about that, given my love of that genre. I shouldn’t be surprised, of course, given the parallel world stuff. I would imagine that most of you new SF-fan subscribers presume this is all some kind of postmodernism, and I don’t really exist. Hmm. Now that raises some intriguing possibilities for furtive mischief. I shall have to consider that one.

I also have some ‘conspiracy theorists’ – I love these people too. I would imagine that section of my lovely new subscribers is of the opinion that I am some weird new psyop they still haven’t gotten their poor heads around yet. Cool! [Careful, Katrina. You don’t want to encourage them. Oh really? That’s not what you were saying before!]

So, let’s try and merge all that, shall we?

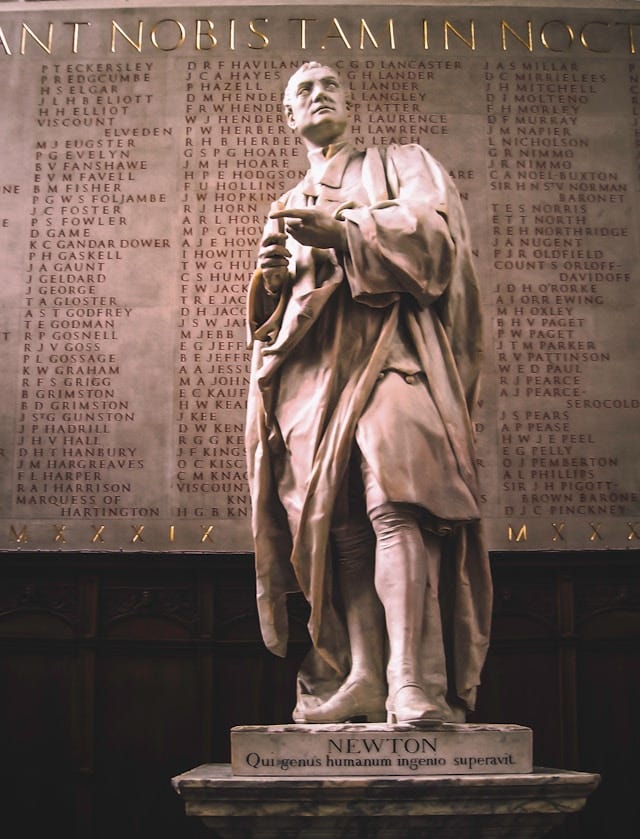

[That’s Isaac Newton’s Apple Tree at Trinity, in case you were wondering]

Anyhow, it behooves me to please my new subscribers, so please them I shall. The best way, I think, for me to start doing that, aside perhaps from telling you a load of stuff about my movies (like I said, I like SF), including our version of Star Wars (this includes an entire new saga you don’t have), is to introduce you gently as it were by telling you some more about our DEXOS.

As I said in Part I, DEXOS is an acronym for the Department for Exo-Studies here at Cambridge. In which case, I should really tell you about extraterrestrial stuff, shouldn’t I? Seeing as that’s its primary directive, after all.

In terms of our own space exploration, I believe I did cover the basics in Part I. We concentrate on a combination of interplanetary probes, exoplanet studies, and human space exploration using artificial gravity through centrifugal force. I don’t need to explain any of that. There are two other related aspects here, though, which I didn’t really mention in Part I. The first is researching new forms of propulsion, the ultimate aim of which, naturally, is to make interstellar travel feasible. By interstellar travel that would not, initially, involve human travel. We are envisaging probes which would need to reach a velocity of at least 0.1 lightspeed at a bare minimum. Even then it would take some 43 years to reach the nearest system, Centauri (it’s a triple star system around 1.3 parsecs/4.3 lightyears away, in case you didn’t know – it’s the same in our world, by the way), and the chances are we would’ve improved on that velocity during that time. So we may as well wait. We also wanted to decelerate the spacecraft on approach to the system so Mothership can then send baby probes to take up orbit around all those planets (yes, of course they’d have communication devices and understand the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis; Kay does). Later, we would include a large rotating habitat module and send people there. And Kay too, most likely.

Think Project Daedalus, with some cool little extras. I did mention we have fusion power, right? Using deuterium and helium-3? Sure I did.

And this is indeed what we decided to do. Halving that time to around 20 years is more acceptable, although still quite long for most impatient people. But given how impatient people can be, we’re not going to wait until we’ve got point-five. Still, until we get to point-five we’ll be concentrating only on probes to the nearest hundred stars, give or take (which is a distance of around 17 lightyears or so). In terms of distance, by the way, we have somewhat arbitrarily decided to define galactic sectors as spheres of roughly 50 lightyear radius. Why? Well, you might say why not, but actually it makes a lot of sense if you think in terms of a combination of maximum achievable velocity and natural lifespan of an intelligent organism like a human. So, if we say a human lives for 100 years, and we generally travel at, say, 0.5 lightspeed, then a single human can travel 50 lightyears in that lifetime. You can clearly see the limitations there. Furthermore, those sorts of limitations have political ramifications. Likewise, it creates a ‘point of no return’ – defined as the point beyond which, if you turned and headed back home at maximum velocity you would be dead before you got there. That’s the ultimate psychological barrier for a spacefaring species, and a lot of people think it has spiritual ramifications too, if we are bound to our homeworld by an astral silver cord.

This guy would probably have accepted such a proposition, given his affinity for the mystical:

[That’s also at Trinity]

See, didn’t I say you SF fans would like me!

Well, you’ll like me even more soon enough.

Before I move on to the extraterrestrial intelligence question, I’ll just wrap up the propulsion research side of things by saying that we are fairly confident of being able to send a probe to the Centauri system at 0.2 lightspeed by around 2035-2040, give or take. So if I was in my world, even aged forty-nine now, I could very well live long enough to see the video footage of what that third planet really looks like. And, naturally, what all those intelligences look like too. And their space stations.

But in this world, I hate to tell you, you will not know. And mainly because you won’t be allowed to know. That’s not just because the monsters who control this dystopia wouldn’t let you know, more importantly it’s because those monsters are responsible, I am absolutely certain, for the ETIs placing this system under quarantine. And that means, no interstellar travel. The reason for this should be obvious. Think about it from the ETI point of view – they see your monsters as a very serious threat, should they ever achieve more advanced technology (research which they would prevent, through AI-directed nanosabotage most likely). They also, incidentally, would see you as a threat for not doing anything to remove those monsters, and for indulging in their manufactured racism and nationalism (if you are racist against members of your own species, well, you can work out the rest yourself). You do, after all, outnumber them by at least 99-to-1. Perhaps coming to understand that you are quarantined and will never be allowed to leave this system and see what’s out there might just provide you sufficient motivation to do what must be done. And maybe the very survival of your species depends on it, if quarantine is an extinction sentence.

So I was not surprised when I arrived in this world and quickly ascertained its dystopian nature to find that you don’t know anything about our galactic sector, or even the Centauri system. At least, not publicly, anyway. I can pretty much assure you that the cabal definitely know.

They have a need to know, after all.

And yes, it really must make them mad to be forced to realise that there’s always a bigger fish.

Whilst we’re on the subject of Professor Frank Drake (I’m getting ahead of myself here – call it time travel), it’s time to take a little detour before I start discussing signals. This is the same Drake who formulated the so-called Drake Equation, which is a kind of thought experiment designed to assist speculation regarding the number of intelligent civilisations in the galaxy. It does this by invoking a number of variables, like number of stars, number of stars with planetary systems, number of systems with habitable planets, and so on. Obviously the result you end up with depends entirely on the arbitrary numbers you assign to each variable. You may think that seems reasonable. Well, it certainly does if you’re thinking about the beginnings of life in the galaxy, but after 7-8 billion years’ worth of galactic disc habitability, it comes across as amusingly quaint and psychologically immature.

It didn’t take DEXOS very long at all to add the most important variable of all, which is life itself. More specifically, intervention. By intervention we mean easily understandable concepts like terraforming, or even planetary system engineering. Likewise, seeding planets with biological life, and then protecting that life from extinction level events, like asteroids. Did you know, for example, that most astronomers calculate the chance of an ELE asteroid strike on this planet to be around 1 in 50 million? It’s one of the most exciting and ominous facts in the whole of astronomy, as far as DEXOS is concerned. But you won’t see the ramifications of it being mentioned in your world. See, 600 million years ago this planet was a snowball. Then it wasn’t anymore and you had the pre-Cambrian explosion of life. So, in the intervening 600 million years there should have been about twelve ELE asteroid strikes, give or take. But there’s only been one. And even that wasn’t total extinction. This becomes even more of an ominous fact when you consider that the Centauri system is, as it happens, about 600 million years older than this one. Maybe I’ll let you do the rest of that math.

To understand all this you simply need to think from a spacefaring lifeform’s point of view. Especially such a lifeform in the earliest period of habitability in the galaxy. Say they develop interstellar travel and discover there aren’t really any other intelligent lifeforms out there. If I was them, I’d start creating life and maintaining habitability and so on. Sure, terraforming doesn’t happen overnight and you need a little spiritual altruism, because you may never see the results of your handiwork, but by that stage, such a lifeform would be spiritual and altruistic, and understand that they, even if they are alone, are part of a greater galactic whole. There is, believe me, no such thing as some ridiculous Star Trek ‘prime directive’ about never interfering. Aside from anything else, a policy of non-interference would mean you just stand by and watch whenever some evil, fascist imperialist lifeform comes along and develops interstellar travel and the CIA and fucking Death Stars and such like. How dumb would you have to be to allow that to happen, eh? That’s the purpose of the interventionist policy. It keeps the peace.

Anyway, even if you, yourself, will not live long enough (as a species) to oversee your handiwork, your artificial intelligence will. So you give it a whole load of robots and such like and the ‘protection against ELE asteroids’ subroutine and just let it get on with it. Fast forward a billion years and you have a galaxy teeming with life.

Such a situation, psychohistorically, which is more than just psychologically believable, it’s psychologically inevitable, is what is known as the Zoo Hypothesis. Which simply states that the galaxy is teeming with life. In our world, and certainly at DEXOS, you will be hard pressed to find a scientist who disputes this hypothesis. This is not only because we have discovered other lifeforms in our own system (Venus, Mars, moons of Jupiter and Saturn), but there’s also the ETI signals and the data from the Jocelyn Bell-Burnell Space Telescope when it was pointed at Centauri in 2016 (along with our other L2 interferometers). Given that I am perfectly aware of this technological capability, it strikes me that the only explanation for your so-called ‘James Webb Space Telescope’ takes on the form of yet another ‘conspiracy theory’. Namely either 1/ its capabilities are far better than the public knows about (i.e. it’s good enough to detect little rocky planets in the habitable zone of Alpha Centauri) or 2/ it’s as poor as they say it is but they have their own, secret telescope an order of magnitude better and they are hiding the data from you, or 3/ it doesn’t even exist and they’re just making up data (possibly from a version of option 2). Given the existence of that notorious ‘Brookings Report’ which advised that knowledge of extraterrestrial intelligences should be concealed from the public, option 2 there seems eminently credible.

But so does option 1. The cabal, after all, as I say, really do have a need to know. They also have a need to know what the ETI’s intentions towards them are. Remember that the cabal do, indeed, know perfectly well they are an evil dystopian cabal. They may habitually practice self-deception in that kind of regard but they do in fact understand at least how others perceive them and their actions. Namely that such actions are ‘not morally good’. Hence the need to conceal such actions (and hence the existence of conspiracy theories about it). That perception doesn’t just apply to the general human population, it also applies to any ETI that may be watching.

Think about it. If you were planning an exoplanet-hunting telescope you would make damn sure it was at least good enough to detect habitable planets in the habitable zone around your nearest neighbour star, wouldn’t you? Especially when that star, Alpha Centauri, which is similar as can be to ours, has to be one of the most obvious and best candidates for a habitable system. You would do what we did, which is set your telescope at L2 and just point it for a year at your nearest neighbour and then work outwards star by star from there. The JWST, if we are to believe its capabilities, is one of the most monumental and pointless wastes of money, time and effort in the history of astronomy. It can, apparently, only detect Neptune-sized planets near the habitable zone, or up to 3 or 4 AU – and the laws of physics should tell you that doesn’t happen in planetary system formation (it may happen in the early stages but it’s not stable), and that such planets, four times the size of this one, would not be habitable. Again, they really do want you crawling in the gutter rather than looking up at the stars, at your long-term future as you should be.

Is all of this not psychologically obvious? Does it not tell you everything you need to know about the cabal? Because it bloody well should do.

You should also know that we have an unlimited budget for all this space exploration stuff, including the search for exoplanets. In your world, they continue to cancel projects because of something they call ‘not enough money’. Remember the cabal are all trillionaires, so you can bet they have secret research projects, which, out of aforementioned necessity, include exoplanet hunting. It’s not, in fact, difficult to imagine what they have. Simply look at some of your ‘cancelled’ projects. Space based interferometry is one such. Interferometry simply meaning combining multiple telescopes to act as one larger one. Two examples of cancelled projects are here (the ESA’s ‘Darwin’ concept, also positioned at L2 – note well it would’ve been an order of magnitude better than James Webb) and here (NASA’s ‘Terrestrial Planet Finder’). Then there’s the ‘hypertelescope’ concept, invented by a French dude called Labeyrie. Needless to say, we’ve had those concepts operating for ten years now, with beautiful results. This, remember, is what they are keeping from you. And it really, really should make you angry. Your America spends a trillion a year on making war against their own species, remember. Think what amazing stuff you could have, and what amazing stuff you could know, for all that money.

So now we come on to the related issue of the so-called ‘Fermi Paradox’. This alleged paradox was framed by Enrico Fermi and asks the question, ‘if the zoo hypothesis is correct, why haven’t we seen any evidence of aliens’. This question deserves attention. Leaving aside the obvious riposte, ‘there is evidence, but you’re just too blind to bloody see it’, there is a really, really brilliant and revealing psychological answer to that question which formed the subject of one of the best papers produced by DEXOS (at least in my opinion – and yeah, I am a pretty opinionated kind of girl; as you have undoubtedly noticed). This paper suggests that different lifeforms have different answers to that question and, indeed, different versions (or framings) of the question itself. It all depends on the socio-cultural identity, or ideology, of that lifeform. To put it in more ironic terms, the reason why Fermi & the Gang couldn’t see any evidence was not because of anything to do with extraterrestrials, and everything to do with Fermi & the Gang. In other words, they didn’t even think for one minute to include themselves in the answer to the question!

The paper concludes with a re-formulation of Fermi’s original question, which goes something like, ‘what is it about us that we haven’t seen any evidence of extraterrestrials?’. Fermi, then was not thinking at all about the most crucial question ‘what must the aliens think of us’. He was looking ‘out there’ from his own paradigm, he was not looking from the extraterrestrials’ point of view. So that crucial question can be rephrased as ‘why do we have a Fermi Paradox?’ or ‘why haven’t the extraterrestrials given us evidence of their existence?’.

On a more humorous note, as one mischievous postgrad student quipped, there’s also the adolescent version of the Fermi Paradox, which goes ‘why doesn’t anybody like me?!’.

As you can hopefully understand, these are the kinds of amazing philosophical discussions that take place all the time in the hallowed alehouses of Cambridge these days (not to mention the diametrically unhallowed secret meeting halls of the notorious Cambridge Apostles – sorry, that was an irresistible in-joke).

[That’s the Mullard Radio Observatory at Haslingfield, just outside Cambridge]

If you start pursuing that line of thought then it becomes far easier not only to answer that Fermi Paradox question – by healthy self-reflection – but you can also start speculating about 1/ if and when previous contact occurred (ancient aliens and such like – which is a subject I for one am totally fascinated about) and 2/ the specific nature of the ‘interventionist’ policy. Specifically, that is, in how it must be tailored to the socio-cultural identities of specific intelligent (but not yet spacefaring) lifeforms. Furthermore, because this provokes ‘self-reflection’, if you examine human history it becomes quite clear why ‘overt’ contact has not been carried out in full view of the general population at least since very ancient times when humanity was not so, shall we say, fucked up.

Of course I am being provocative. I mean ‘not racist’, ‘not scared of the other’, and, simply, ‘more spiritual’. Like in Atlantis, if you believe in that kind of thing.

Instead, an extraterrestrial lifeform, having studied a species remotely (and with nanosurveillance), would then discuss decisions about whether to make contact, and if so, how to make contact (tailoring it to the species, that is). In the case of modern humans, then, clearly they had to be psychologically creative about it, perhaps out of a combination of sensitivity and pure mischief. It would have been clear to them that the likes of Fermi, Drake, Sagan et al. were simply not psychologically capable of such overt or direct contact. If they had been, they would not have asked such an inane, psychologically immature question like the Fermi Paradox, and their version of the ‘Drake’ equation would’ve thought about the issue in a much deeper way and not confined themselves to the kind of ignorant materialism and arrogance of ‘pure scientism’.

At some point I shall have to amuse you with the psychological (or psychohistorical, even) analysis of the so-called ‘Golden Record’ from the Voyager 1 probe (it’s also in my movie Meet the Paschats). For now, though, perhaps it simply suffices to point you towards the letter signed by then American President Carter, which stated ‘we hope to one day join a community of galactic civilisations’ – this is evil America we’re talking about here, remember, whose foreign policy consists in racism, colonialism, resource theft, exploitation, the instigation of war, conflict, suffering, torture, and genocide. Would you, reader dear, after all, allow a country with a CIA to join a ‘community of galactic civilisations’? No, neither would I. That would be dumb.

Hopefully now, you can see what I’m getting at.